One of my most memorable expeditions was the summer I spent in Pirea, a city-state in the northeast of the Alissian mainland. The rocky soil there will grow nothing but weeds. Ninety percent of the population’s food comes from the sea. Their survival hinges on the success of a six-week fishing season in early summer.

One of my most memorable expeditions was the summer I spent in Pirea, a city-state in the northeast of the Alissian mainland. The rocky soil there will grow nothing but weeds. Ninety percent of the population’s food comes from the sea. Their survival hinges on the success of a six-week fishing season in early summer.

That period is when a confluence of rising water temperatures, ocean current changes, and yearly spawning brings the shoals of deepwater fish into range of Pirean fishing vessels. Virtually every man, woman, and child over the age of ten contributes.

Inexperienced as I was, I had no trouble finding a berth.

So it was that I found myself learning the ropes — literally, every rope required to operate the vessel and its nets — as we sailed south and east from the Pirean shores. My captain’s name was Arturo, and it was his twenty-ninth season piloting a boat. His instincts at where and when to drop the nets were good enough that I suspected magic, though I couldn’t prove it. We never hauled up a load that was less than bursting with shimmering, silver bodies.

But we were not the only ones drawn to the hunt.

The presence of so much food, and our frenzied hauling of nets, caught the attention of other predators. The porpoise-hunters are perhaps the easiest to understand: they’re a cross between a shark and a dolphin. These intelligent pack hunters travel in pods of ten or fifteen individuals. On a good day, they were in the mood to cooperate, and drove the thickest schools of fish into our nets. Arturo was careful to give them a share of the catch in return.

Once, we happened on a smaller fishing vessel, a single-masted Landorian sloop that appeared to be drifting. No one remained on board, though the bite-marks and blood told a gruesome tale. When I asked the captain what had happened, he shook his head and spat. “Didn’t pay the porpoise-hunters.”

Alissia has classical sharks, too, more species of them than I could ever hope to classify. The other fishermen were quick to point out the ones that were particularly dangerous. The whiptail was the most despised of these: their bodies twenty feet long, and their tails another eight feet beyond that. Lean, muscular, and capable of destroying an entire net with their thrashing. Just a mean creature, the kind that would lurk in the shadow of our bow in hopes of catching a sailor unaware near the rail.

Their tails make a high-pitched whistling sound when the sharks leap from the water. You learned to recognize it. To throw yourself flat on the deck and whisper a prayer. I was not always fast enough. Once, a tail caught me on the shoulder. Cut me like a knife. It bled for days afterward.

There were other horrors, too: packs of razor eels that swarmed the hull and had to be fought off with wooden staves, a great floating jellyfish that drifted unerringly toward us on the wind. But the one that haunts me most might surprise you.

There were other horrors, too: packs of razor eels that swarmed the hull and had to be fought off with wooden staves, a great floating jellyfish that drifted unerringly toward us on the wind. But the one that haunts me most might surprise you.

We were three weeks out from port when the wind died. Becalmed, we drifted at the mercy of the ocean currents for two days. It carried us to even deeper waters, where we happened on a floating island of kelp. Flowers of every hue and color bloomed all over it — bright purples and pinks and yellows. I was so fixated on these, and the butterflies tending them, that I almost failed to notice the massive shadow beneath the kelp.

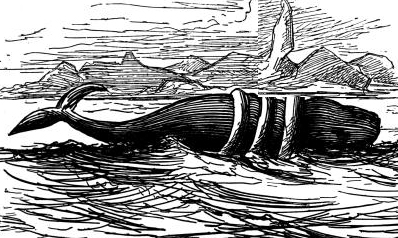

It was a whale, and the largest living creature I’ve ever seen. Easily a hundred and fifty feet long. The leviathan hovered there motionless, and I thought it had died. No. It was alive, in a manner of speaking, but caught in the roots of the kelp island.

These exuded some kind of paralytic toxin, according to the captain, and held the great beast captive while it was slowly eaten alive by the plants above. We drifted close enough that I saw other sea-creatures held by the kelp: a smaller whale, a few sharks, and two porpoise-hunters.

All of them nothing more than plant food, and doomed to drift their last days in the cold waters of the Alissian seas.

Leave a Reply